Landlords and tenants have been preparing to navigate the MEES regulations for some time, but since the regulations now apply to all new leases landlords and tenants can expect arguments about the MEES obligations to form part of the discussion over dilapidations at the end of the lease.

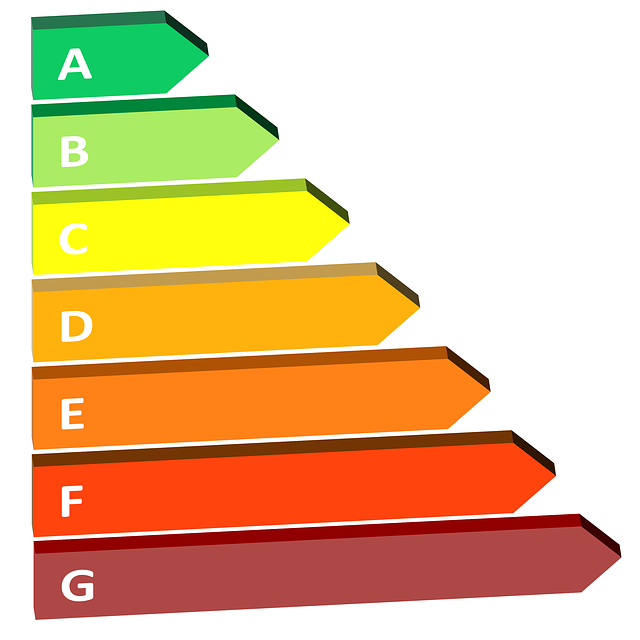

Since 1 April 2018 a landlord of a commercial property with a valid energy performance certificate (EPC) with a rating of F or G must not let the property, unless an exception or exemption applies. A landlord who does so faces financial penalties and may be “named and shamed”. Where there is no exception or exemption to rely on, a landlord of F or G rated property would be well advised to undertake works to improve the energy performance rating before it lets the property to a new tenant.

It is well established that a landlord cannot recover damages from a tenant for a breach of repairing covenants where the repairs will be rendered valueless by works the landlord will do to the premises after the expiry of the lease. This is known as supersession. Tenants of premises with a valid EPC rated less than E (and where an exception or exemption does not apply) will therefore inevitably argue that the landlord’s dilapidations claim should not include works which will be superseded by works the landlord has to undertake in order to re-let in compliance with the MEES regulations. A tenant will argue it should not be liable to repair anything which the landlord is going to have to replace in order to improve the EPC rating of the property so that it can be re-let lawfully.

Commercial properties with an EPC rated F or G might well require improvements to lighting, heating systems or air conditioning in order to reach the minimum standard. If, for example, the landlord must replace the air conditioning system altogether in order to raise the energy efficiency of the building to an E rating, the tenant might be able to argue successfully that it has no obligation to repair the air conditioning at all. In this way the tenant may be able to reduce its dilapidations liability significantly.

Where a property requires improvement to reach an EPC E (or above) rating, there may be different ways to achieve this. The landlord will want to elect which of the inefficient features of the building it chooses to improve and will not want its hands tied by the tenant’s desire to minimise the dilapidations claim. Therefore the landlord needs to be forearmed with advice from an EPC assessor on the most cost effective means of improving the EPC rating in the face of such claims. Similarly, tenants who could make significant savings on dilapidations will also be looking to EPC assessors to advise where the necessary improvements need to be made.

Landlords and tenants should also take advice on the wording of the lease before relying on these arguments to establish whether the repairing and reinstatement provisions impose obligations to make improvements. In every case, the extent of the tenant’s obligation turns on the precise wording of the lease which will ultimately govern whether the tenant can take advantage of MEES to reduce its dilapidations liability at lease expiry.

Of course, dilapidations do not have to be addressed only at the end of the lease. If the property is in disrepair and the lease permits it, the landlord might have grounds to serve a notice of disrepair on the tenant and require the tenant to carry out works during the term. In that case the tenant would not be able to argue supersession and instead could be forced to comply with its repairing obligations during the term. If the tenant fails to carry out the works, and the lease allows it, the landlord could be entitled to carry out the works itself and recover the costs from the tenant. However, if the standard of repair required by the lease means that the property still falls short of the minimum standard, the landlord may still have to undertake works at the end of the term in order to re-let lawfully. Landlords considering serving notices of disrepair should act cautiously and take legal advice because failure to serve the notice correctly and carry out legitimate works could expose the landlord to a claim for damages.

Starting on 1 April 2023, landlords continuing to let properties with a valid EPC which at that point in time is rated less than E will be in breach of MEES unless an exception or exemption applies. This means that a landlord of premises subject to a lease which expires after 1 April 2023 will need to undertake MEES improvement works during the term of the lease in order to continue to let the property lawfully from 1 April 2023. Landlords of such leases should look ahead and see if the lease permits them to pass the liability to upgrade to their tenants during the term in order to avoid bearing the cost of any necessary improvements. Landlords with leases which outlive their EPCs will need to take a tactical view on whether to renew their EPC voluntarily in order to pass on obligations to their tenant (if they can) or allow it to expire so that the regulations do not apply.

The best way to mitigate liability in new leases is to draft leases taking MEES into account. Landlords and tenants should be looking very closely at the wording of the repair, reinstatement, service charge and other obligations in their leases to establish who should pay for MEES improvements.

Stephanie Newton

Stephanie Newton Markus Klempa

Markus Klempa